The Racist Origins of Policing, Prisons, and Immigration Enforcement

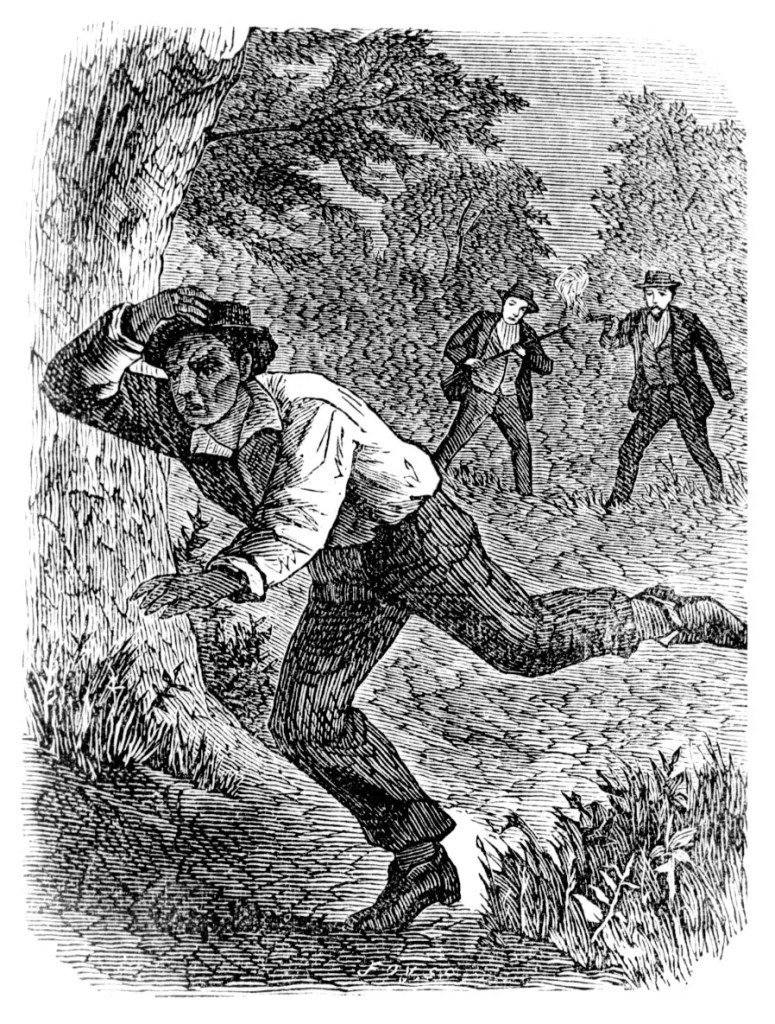

Taking inspiration from the British, centralized municipal police forces in the U.S. can be traced back to the early 1800s, beginning in Boston and spreading to other cities. However, this narrative is incomplete. Michael A. Robinson writes that “The death of unarmed Black men at the hands of law enforcement in the United States is not a recent phenomenon and can be traced back as early as 1619 when the first slave ship, a Dutch Man-of-War vessel landed in Point Comfort, Virginia.” Slave Codes, laws equating enslaved people to property and governing their cruel and inhumane treatment, led to the creation of slave patrols to enforce these laws. The first slave patrol was created in the Carolina colony in the early 1700s. Slave patrols were responsible for apprehending enslaved people who escaped, preventing slave riots, and punishing enslaved people for not adhering to plantation rules, all of which involved inflicting violence on enslaved people. The usage of law and law enforcement to control enslaved Africans was not limited to the slave-holding South, however; legislation was passed in some northern states to target formerly enslaved people who had escaped.

After the end of the Civil War, Southern slave patrols evolved into modern-day police forces. Therefore, policing has explicit origins in protecting the interests of White slaveowners and brutalizing Black enslaved people. Racism and racial violence are indeed embedded in the formation of police forces. This trajectory was continued with the passage of Black Codes and later Jim Crow segregation laws, which were enforced by Southern police forces. Outside of the South, police continued to protect the interests of wealthy white Americans while controlling and brutalizing Black Americans and immigrants.

The 13th Amendment did not completely abolish slavery— rather, it was abolished “except as punishment for a crime.” This served as “state authorization to use prison labor as a bridge between slavery and paid work.” The convict leasing program in prisons enabled the state to “lend” prisoners and their labor to various corporations, essentially making up for the lack of free labor brought upon by the end of slavery outside of the prison system. Coupled with the Black Codes, which imposed harsh sentences on crimes such as vagrancy and loitering, prison populations and prison labor grew exponentially in the post-Reconstruction period.

Immigration was largely unregulated by the federal government until “political anxiety, social tensions, economic fears, religious prejudice, and racism all played important rolesfrom the 1880s to the 1920s as the national legislators piled restriction upon restriction.” The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, the first comprehensive federal immigration legislation, was overtly racist, barring Chinese immigrants solely on the basis of their national origin due to growing anti-Chinese sentiment in the West. Another clear instance of racism within the immigration legal system is the treatment of undocumented individuals— despite the fact that living in the U.S. without legal documentation is a civil offense, undocumented status has been linked with illegality and criminality since the initial rise of undocumented immigration in the 1940s and 50s. In 1996, legislation expanding the grounds on which someone could be deported and narrowing grounds for appeal was passed. When ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) was established under the newly created Department of Homeland Security in response to 9/11, deportations increased even more. Criminalizing the presence of undocumented immigrants, while making it nearly impossible for many immigrants to seek lawful immigration through processes such as asylum, is explicitly racist and anti-immigrant. The fear of deportation not only renders immigrant communities vulnerable but also threatens their socioeconomic and employment statuses.

The Need for Abolition

Racism in policing, prisons, and immigration enforcement is not merely a relic of the past. In 2014, a ProPublica investigation found that young Black men are 21 times more likely to be fatally shot by law enforcement compared to their white counterparts. These numbers show that police killings of Black Americans aren’t an anomaly— rather, these police officers are acting in accordance with the system that was built on brutalizing Black Americans and other minorities. As abolitionist scholar and practitioner Mariame Kaba wrote for the New York Times, “So when you see a police officer pressing his knee into a black man’s neck until he dies, that’s the logical result of policing in America. When a police officer brutalizes a black person, he is doing what he sees as his job.”

Contrary to popular belief, police and prisons do not deter crime. In 2016, a group of researchers conducted a systematic review of 62 studies and 229 findings of police force size and crime, concluding that “the overall effect size for police force size on crime is negative, small, and not statistically significant.”A 2022 report by Catalyst California and the ACLU of Southern California found that “U.S. police spend much of their time conducting racially biased stops and searches of minority drivers, often without reasonable suspicion, rather than ‘fighting crime.’” Instead, they merely respond to crime after the fact and impose punishments, and what they truly aim to protect is capital. “Businesses and private developers rely on police to help establish environments conducive to consumption,” writes Bronwyn Dobchuk-Land and Kevin Walby.

In place of a robust network of social services, imprisonment serves as a response to issues such as poverty, substance use, and interpersonal violence. They do not serve as places of rehabilitation— rather, they are overcrowded, violent, and inhumane environments. Prisons and jails are known for their inadequate mental and physical healthcare. More than half of all Americans in prison or jail have a mental illness, and prison staff and administrators often resort to physical abuse and solitary confinement as a response to people’s mental health struggles. Over 60,000 people are held in solitary confinement in the U.S, being isolated in their cells for 23 hours per day. Suicides among people held in isolation account for almost 50% of all prison suicides.

Increasingly, prisons in the United States have become privatized. In 2022, 90,873 people were incarcerated in private prisons, constituting 8% of the prison population, and this number is steadily growing. Private prisons prioritize profit over the well-being of incarcerated people and benefit from their continued imprisonment. Aside from the “corrections” industry itself, other companies have found ways to profit from incarceration— in 1995, Dial Soap sold $100,000 worth of product to New York City jails alone.

The most evident way that policing, prisons, and immigration enforcement are connected is through what is known as the traffic stop to deportation pipeline. Traffic stops are the most common way that civilians interact with the police, and they are also rampant with racial biases. In 2019, 20,000 people who had been deported by ICE had been convicted of traffic-related offenses. In many places, local police work with ICE, checking the immigration status of people they pull over. If they are undocumented or a legal permanent resident convicted of a crime, they can be handed over to ICE. State and local prisons and jails have contracts with ICE to use parts of their facilities as ICE detention centers. In Massachusetts, ICE detainees are held at Plymouth County Correctional Facility, often indefinitely until their deportation. The latest contract signed last year says that ICE will pay the Plymouth Sheriff’s Office an increased amount of $215 per detainee per day, creating a financial incentive for immigration detention.

To many, abolition seems far too drastic. Why not simply reform police, prisons, and immigration enforcement to make them less harmful? But as illustrated, racism, as well as other forms of oppression such as misogyny, ableism, xenophobia, homophobia, and transphobia, are all embedded into these systems. These systems are, by nature, designed to be violent and oppressive. Prisons will never be a truly successful form of rehabilitation because of the inherent trauma of being imprisoned. As the authors of The Price of Punishment: Prisons in Massachusetts write, “A prisoner’s first struggle is to survive until release. That struggle alone takes too much attention and too much mental energy to leave much time or desire for taking part in programs of rehabilitation.” Police reforms often involve inflating the budgets of police departments even further and target singular “bad apples” as opposed to the system as a whole. Regardless of reforms made to the immigration enforcement system, it still relies on the premise that certain people are undeserving of residing in the United States. The only way to eliminate the harm caused by these systems is to dismantle them entirely.

The Origins of Abolitionist Mvements

As long as systems such as slavery, segregation, and prisons have existed, so have radical imaginings of a world without these systems. Moreover, these imaginings have always existed close to home in Massachusetts— Boston-based abolitionist David Walker’s 1829 work “An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World” is one of the most crucial anti-slavery writings of the 19th century, as it called for global solidarity among people of color and drew attention to the abuses suffered by enslaved Black people in the U.S. Fast-forwarding about a century-and-a-half, the Combahee River Collective, a Black feminist lesbian group in Boston, was formed in 1974. The Collective developed the Combahee River Collective Statement, most known for its conception of “identity politics”— they write, “We believe that sexual politics under patriarchy is as pervasive in Black women’s lives as are the politics of class and race. We also often find it difficult to separate race from class from sex oppression because in our lives they are most often experienced simultaneously.” This concept is crucial in abolitionist theory, as it helps explain, for example, why Black, Latina, and Indigenous women are disproportionately incarcerated when compared to white women.

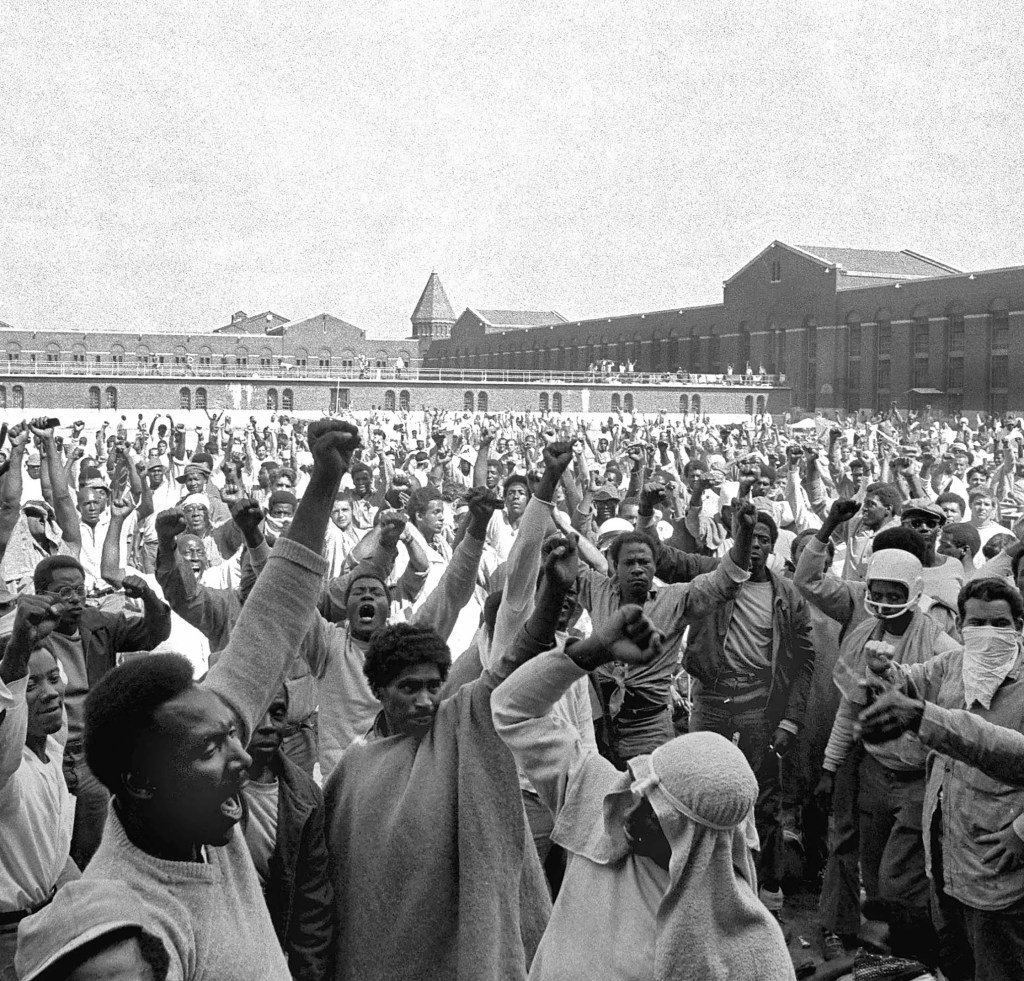

The prison abolitionist movement in the U.S. emerged in the 1970s and 80s, in response to the War on Drugs that exacerbated mass incarceration. When discussing abolition, it is critical to center people that have been directly impacted by the prison, policing, and immigration enforcement systems, while also emphasizing their accomplishments and contributions to the movement. For example, the 1971 Attica Prison riot was a crucial moment in history, raising awareness of the cruel conditions prisoners are subjected to. Arthur Harrison, who was incarcerated at Attica during that time, told NPR News about the particularly abysmal treatment of Black incarcerated people, saying, “It reminded me of the things I used to hear about on plantations in slavery. They treated us like we weren’t human.” On September 9, 1971, prisoners took control of Attica Correctional Facility, and they soon after presented a manifesto to New York State officials. They wrote, “We, the inmates of Attica Prison, have grown to recognize beyond the shadow of a doubt, that because of our postures as prisoners and branded characters as alleged criminals, the administration and prison employees no longer consider or respect us as human beings, but rather as domesticated animals selected to do their bidding in slave labor and furnished as a personal whipping dog for their sadistic, psychopathic hate.”

A foundational abolitionist text, “Instead of Prisons,” was published by the Prison Research Education Action Project (PREAP) in 1976. In this handbook, PREAP aims to form a collective ideology around prison abolition and outlines actionable steps, such as moratoriums on constructing new prisons and jails. Their three-pronged abolitionist ideology advocates for “(1) economic and social justice for all, (2) concern for all victims and (3) rather than punishment, reconciliation in a caring community.” Another key concept in abolition is The Prison Industrial Complex (PIC), is a term coined by Angela Davis “to describe the overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisonment as solutions to economic, social and political problems.” The PIC includes police, prisons, and immigration enforcement, and works to produce fractured communities, a lack of social services and resources, marginalization, and further inequality.

Critical Resistance, one of the first abolitionist organizations in the U.S., was formed in 1997 by Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Angela Davis, and others to challenge “the idea that imprisonment and policing are a solution for social, political, and economic problems.” Their work includes prisoner solidarity, political education, halting prison/jail construction, and police resistance campaigns. In 2001, Critical Resistance, along with INCITE!, another abolitionist organization, released a joint “Statement on Gender Violence and the Prison Industrial Complex.” This statement explains how criminalization does not actually deter gender-based violence. For instance, indocumented women have reported violence only to be deported, and women who have killed or harmed their abusers have ended up arrested and imprisoned. The authors explain that in addition to interpersonal violence, women face state violence from prisons and police. However, it is also true that anti-prison movements do not adequately addressed the everyday violence that women and LGBTQ+ people face. The statement argues for community-based and restorative justice approaches to addressing violence against women and LGBTQ+ people without reliance on the carceral system.

Abolition is not a stagnant philosophy, but rather, something that is always growing and evolving. As the PIC finds new ways to brutalize and terrorize people, abolition offers new solutions and imaginations of a world without these harms. Most importantly, abolition is reliant on love, care, and solidarity among and across communities. This page by no means encompasses the entirety of abolitionist history and scholarship— rather, this is intended as an introduction and a starting point for further research and exploration. Below is a small reading list that explores some of these topics in more depth. Additionally, please visit the “Abolitionist Projects” page to learn more about how abolition is being currently practiced in Massachusetts.

Suggested Readings:

Abolish ICE, Natascha Elena Uhlmann

Abolition. Feminism. Now., Angela Y. Davis, Gina Dent, Erica R. Meiners, and Beth E. Richie

“Amnesty or Abolition? Felons, Illegals, and the Case for a New Abolition Movement,” Kelly Lytle Hernandez

“Attica Futures: 21st Century Strategies for Prison Abolition,” Angela Y. Davis

Becoming Abolitionists: Police, Protests, and The Pursuit of Freedom, Derecka Purnell

Decarcerating Disability: Deinstitutionalization and Prison Abolition, Liat Ben-Moshe

“Slave Patrols, ‘Packs of Negro Dogs’ and and Policing Black Communities,” Larry H. Spruill

“Queering Prison Abolition, Now?,” Eric A. Stanley, Dean Spade, Queer (In)Justice